Twenty-five years ago Tom Frank and

friends started a small journal in Chicago called The Baffler. Like his first

book, The Conquest of Cool, the journal limned the many ways

cultural authenticity has been co-opted, branded, and regurgitated by

corporations and institutions.

There was a lot of subject matter to

work with in Millennial capitalist America. The magazine struggled, and even took a break for awhile. But most of the early issues, some of which

have been anthologized, stand up amazingly well. If anything, the corporate onslaught has

become even more refined and insidious.

Recently The MIT Press picked up

distribution of the journal. The Baffler website has been spiffed up, its back on a three times a year publishing schedule, and

the roster of contributors just keeps getting better. There’s really nothing like it in the world

of cultural and political long-form journalism.

And for twelve bucks!

The 25th anniversary

edition of the magazine, just out, is fantastic. I highly recommend that you stop reading this

right now and go out and get yourself a copy and read that instead, cover to

cover. But if you need nudges, here are

a few of the sacred cows smashed in this issue:

1)

In “Academy Fight Song,” Tom Frank shows “how virtually every aspect of

the higher-ed dream has been colonized by monopolies, cartels, and other

unrestrained predators. The charmingly naïve

American student is now a cash cow, and everyone has got a scheme for slicing

off a porterhouse or two… ours is a generation that stood by gawking while a

handful of parasites and billionaires smashed higher ed for their own benefit.”

2) “Facebook Feminism, Like it or Not”

is a much needed takedown of Sheryl Sandberg’s phenomenally successful Lean In, by feminist scholar and

journalist Susan Faludi. “Never before

have so many corporations joined a revolution,” Faludi writes. “Virtually nothing is required of them- not

even a financial contribution.” The transcript

of her attempt to get some questions answered by the Lean In PR department is

sad and hilarious. (Example: “Q: Would

you encourage a Lean In Circle to picket a discriminatory employer?” A: blah blah blah blah blah.)

3) In “Networking into the Abyss,” a

pointed and genuinely Menckenesque critique of the altcult mecca South by

Southwest, Jacob Silverstein efficiently eviscerates this trendy marketing

event. “During SXSW, Austin becomes a

money-soaked mélange of hyper-consumerism and techno-utopianism… the marketing

machine doesn’t only want to sell to you; it wants you to sell your own

networked persona on its behalf.”

4) In “All LinkedIn with Nowhere to

Go” Ann Friedman makes mince meat of the ubiquitous get-ahead site, and its

philosophy of wish fulfillment as business model. “The roots of the LinkedIn vision of

prosperity-through-connectivity lie in the circular preachments of the

positive-thinking industry,” she writes.

4) In “All LinkedIn with Nowhere to

Go” Ann Friedman makes mince meat of the ubiquitous get-ahead site, and its

philosophy of wish fulfillment as business model. “The roots of the LinkedIn vision of

prosperity-through-connectivity lie in the circular preachments of the

positive-thinking industry,” she writes.

5) In “Street Legal: The National

Security State comes Home,” Chris Bray makes a bone-chilling case that “the

contest between the centralization and decentralization of information is the

real culture war of our moment.”

6) The rise of the right-wing think

tanks is explored in all its depressing glory in Jim Newell’s “Good Enough for

Government Work: Conservatism in the Tank.”

“The perpetually aggrieved American right can rest easy: the

conservative movement has, indeed, won the war of ideas.”

7) In part, as Ken Silverstein

explains in “They Pretend to Think, We Pretend to Listen,” because of the

corporate takeover of liberal think tanks!

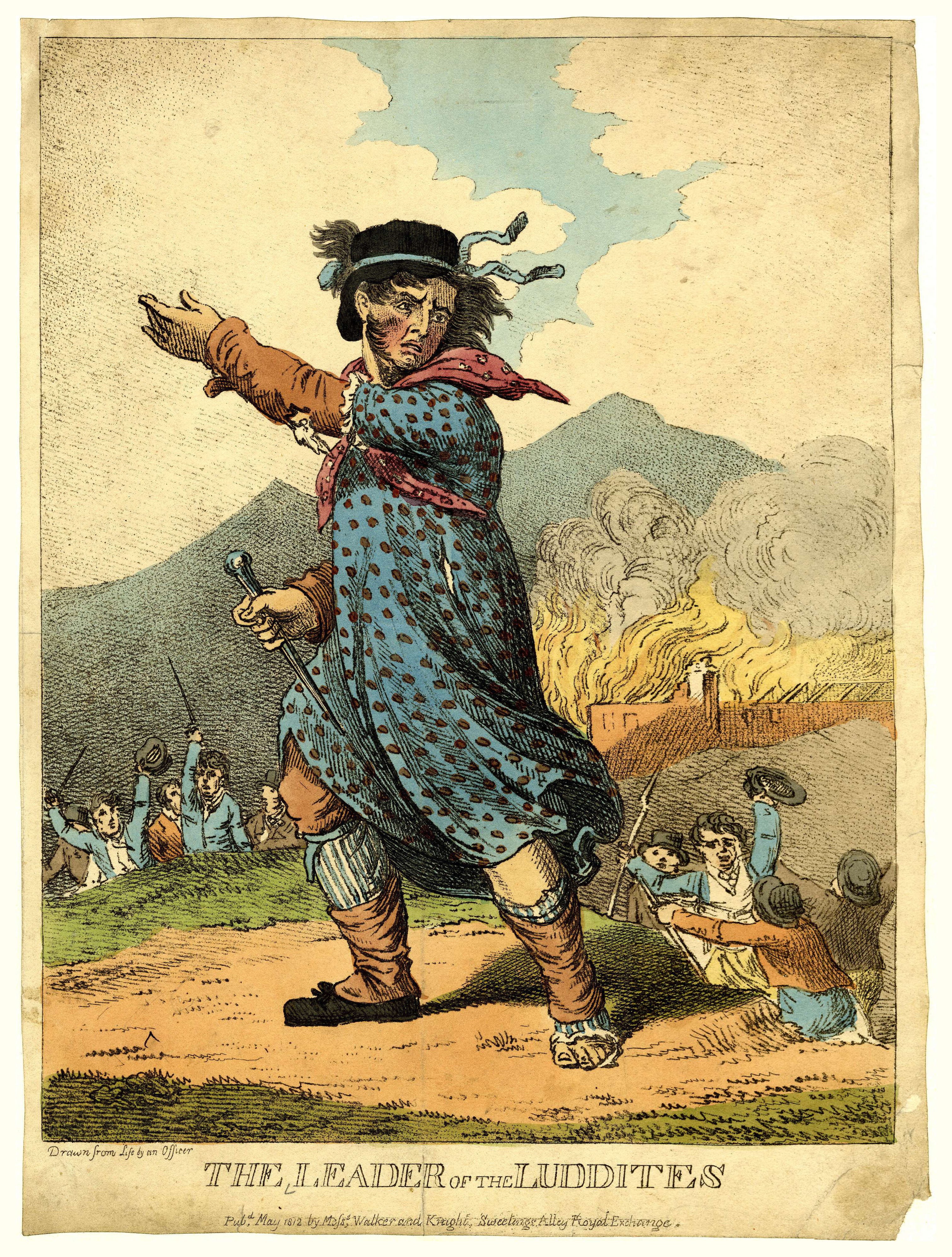

8) In “A Nod to Ned Ludd,” (worth the

price of the magazine alone), Richard Byrne does a huge service by illuminating

the true story behind a term we throw around as if we knew what it meant: “luddites.” Just about everything you think it means is

wrong.

9) “On Wittgenstein’s Steps” is a

surprising and lovely rumination by Croatian writer Dubravka Ugresic on

pigeons, sculptures, and the meaning of public monuments in a time of political

transformation.

10) And in “Sacking Berlin,” Quinn

Slobodian and Michelle Sterling mourn the disappearance of the whimsical, playful,

authentic Berlin that emerged post-1989 and its replacement by “branding, clicking, swiping… a

privatized Berlin.” They lament that “the

monuments of East Germany have been demolished, social services have been sold

off, and with them have gone the memory of the city as a place of shared public

goods.”

10) And in “Sacking Berlin,” Quinn

Slobodian and Michelle Sterling mourn the disappearance of the whimsical, playful,

authentic Berlin that emerged post-1989 and its replacement by “branding, clicking, swiping… a

privatized Berlin.” They lament that “the

monuments of East Germany have been demolished, social services have been sold

off, and with them have gone the memory of the city as a place of shared public

goods.”

And there’s more! Poetry, stories, cheeky graphics and cartoons,

book and movie reviews- 162 pages that will make you laugh and make you a

better person. Inquire at your bookstore

or see TheBaffler.com for more info.